Watching, waiting for something to happen. Narratives unfolding across time and space. Imagining, projecting whilst looking at ‘nothing’ — this is the nuclear experience.

And the experience of this art project which considers the slow violence of critical technologies through the lens of the post-Cold War nuclear age.

The central theme of the Long Life body of work — the complex relationship between people, technologies and the environment — cannot be represented directly and only exists in the artwork somewhere between image and viewer.

Titles and/or intertitles offer context and spare historical detail, a discursive connection to the real. The logic of sound and image is spatial and temporal. Aesthetic decisions are determined by the needs of the work at hand.

When faced with the visual absence of people the viewer is the “absent figure expected to improvise its own narrative” about what they are looking at. This absent figure does the work, putting themselves in the picture to complete the work.

Irradiated landscapes

Something else happens by being there. What you see and what’s in front of you aren’t the same thing. You’re being truthful but not necessarily in that (documentary) way and not to that place. Life comes into it.

Long Life (Maralinga) Plant Life (Chernobyl) Plant Life (Dungeness) Long Life (Kazakhstan) Long Life (Kakadu) Connected (Pine Gap)

Between the real, the plausible

and the imaginary

White on White (after Malevich) Radiant When the Wind Blows MARCH Long Life (1) Fieldwork II Fieldwork I Connected (Pine Gap).

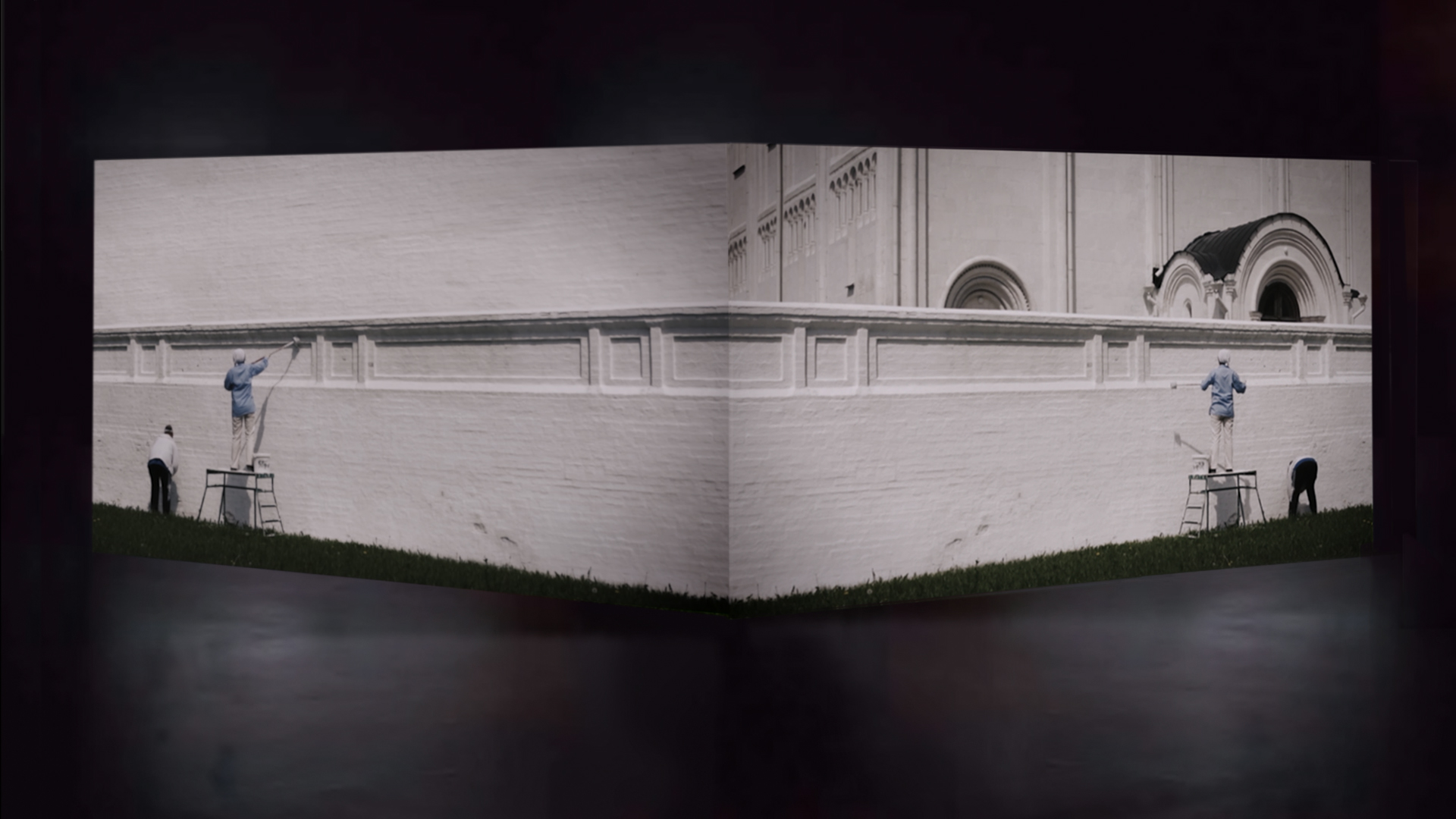

Single-channel HDV, colour, stereo sound. Duration: 03:50. For installation: 1. Single-channel HDV loop, stereo sound. 2. Double-channel HDV loop, stereo sound. Loop duration 04.00. 2017.

In 1918, Kazimir Malevich painted White on White — an off-centre white square angled across a white ground that embodied a sensation of infinity.

In 2005, Admiral Ushakov was named patron saint of Russian Strategic Aviation (nuclear-armed long-distance bombers).

In 2007, St. Seraphim of Sarov was chosen as the patron saint of Russia's nuclear arsenal.

In 2015, two women paint a white wall that surrounds a medieval cathedral in the city of Vladimir.

Single channel looped, vertical installation. Revised version 2017.

Loop duration: 11:40. Stereo sound. (Original version 2015)

Being there. The viewer is placed a corporeal relationship to unfolding scenes of different irradiated

landscapes in the UK, Australia and Kazakhstan. Intertitles offer context and spare historical detail, providing

an anchor to the real.

Single-channel looped installation. Duration 13:00. Stereo sound. 2015

Scenes of apparently mundane nuclear landscapes that still yield atmospheric power. A uranium mine,

nuclear-energy production and defence-related sites, radioactive waste and post-accident and remediated sites.

Two-channel installation with stereo sound. Duration: 1x 7-minute loop, 1 x 2-minute

loop.

2014-2024. A work in progress.

On 19 March, 2014, Vladimir Putin formally annexed Crimea to the Russian Federation.

On 17 July, 2014, Malaysia Airline Flight MH17 was shot down over rebel-held Eastern Ukraine.

On 24 February, 2022, the Chernobyl Exclusion zone was seized by Russian armed forces.

On 4 March, 2022, after heavy shelling by Russian forces, Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant came under Russian

military occupation.

And so it goes.

Listen to Radio National interview by Michael Cathcart with Merilyn Fairskye:

Responding

to Ukraine: New video art has ghostly prescience (31 July 2014)

Single-channel looped installation. Duration: 07:00. Stereo sound. 2013.

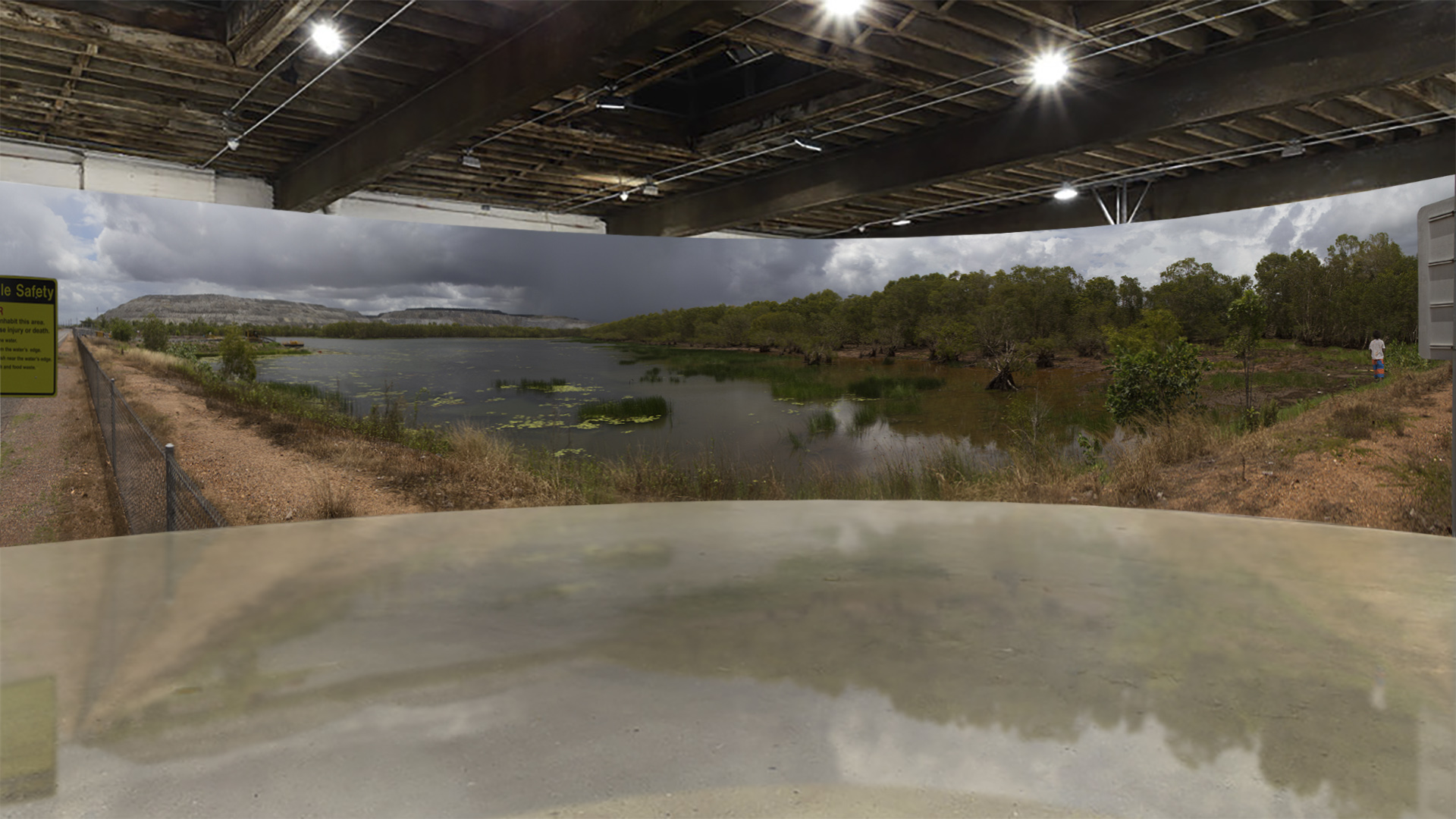

The South Alligator River near the Ranger Uranium Mine in outback Australia is in flood. Waterbirds swoop and

glide across silver surfaces in and out of sync with unmoored radio signals from Sputnik I, the long-lost

satellite. Birds and signals, traces adrift in the ether of flooded, radioactive wetlands.

Single-channel looped installation. Duration: 01:40:00. Silent. 2009.

A single tracking shot, slowed down almost to the point of disintegration. Driving into Chernobyl, past

abandoned houses still contaminated by radiation, and further along, more contaminated houses buried under a

thick layer of clay. Everything covered by a blanket of snow.

Three-channel video installation, stereo sound. Duration: 3 x 03:00 loops.

2009.

Three entombed landscapes inscribed with legends and stories that radiate across time and space — The Three

Sisters, Echo Point, Katoomba; Menkaure's Pyramid, Giza; Pripyat, Chernobyl. "Nothing happens, nor threatens to. We have arrived after the event, in the ruin of time. A world in suspended animation."

Catalogue essay

Three-channel video installation, stereo sound, duration: 3 x 25:00 loops.

2004.

Shot around Pine Gap, Central Australia, this work considers how disembodied and shadowy the experience of being

constantly connected can be. It improvises around the core program of the single-channel video essay Connected and related footage.

"This film is an experiment of real events

with the help of a never-ending story..."

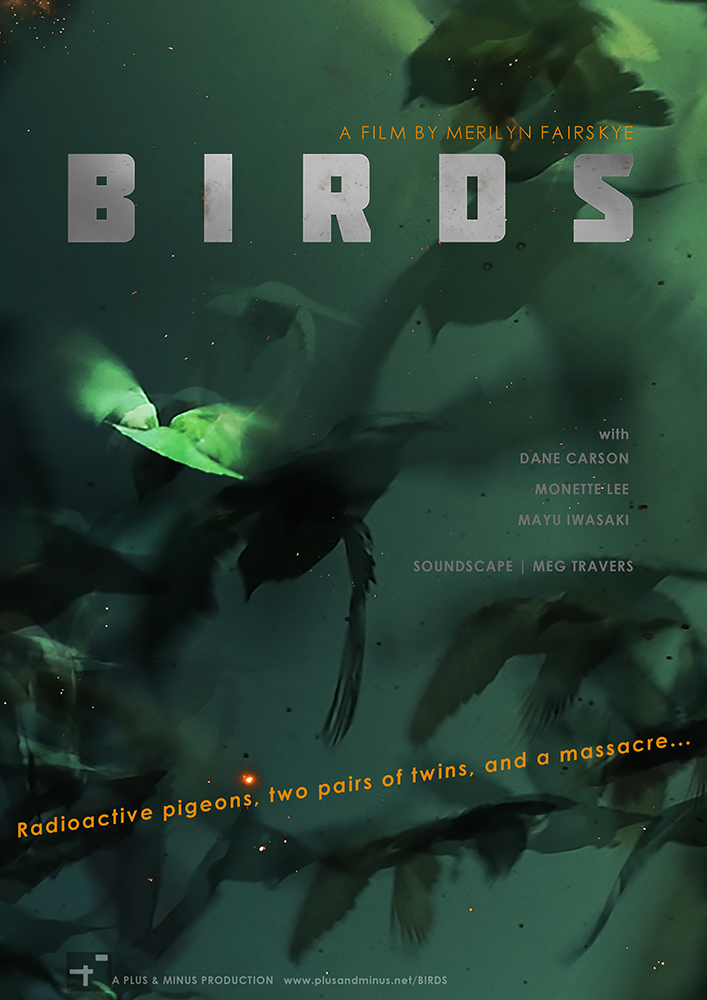

Merilyn Fairskye, 2020. Artist film, single-channel, Duration: 28:27. Stereo sound.

BIRDS is a tale of radioactive pigeons, two pairs of twins and a massacre, set in a seaside village in the shadow of a decrepit nuclear plant. In this blighted environment all is entangled - birds, humans, plutonium - and nothing will be spared.

BIRDS is inspired by real events that took place between 1998-2010 in the area around Sellafield, the large nuclear reprocessing site in Cumbria, UK.

BIRDS trailer

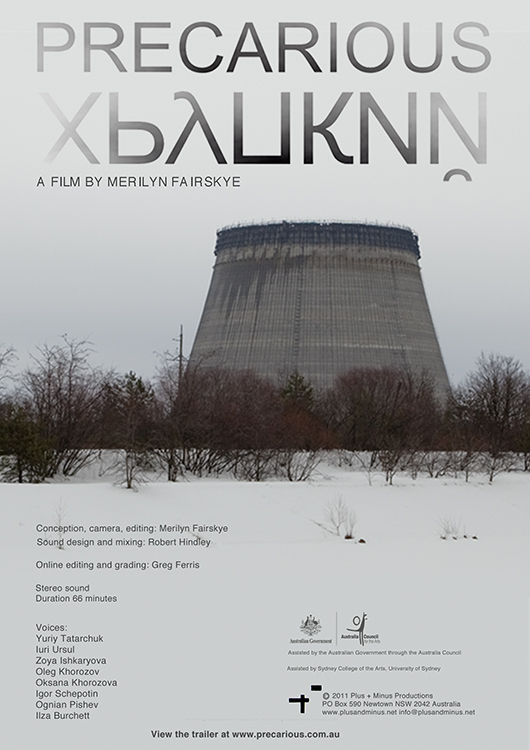

Merilyn Fairskye, 2011. Artist film, single-channel. Duration: 01:06:00. Stereo sound.

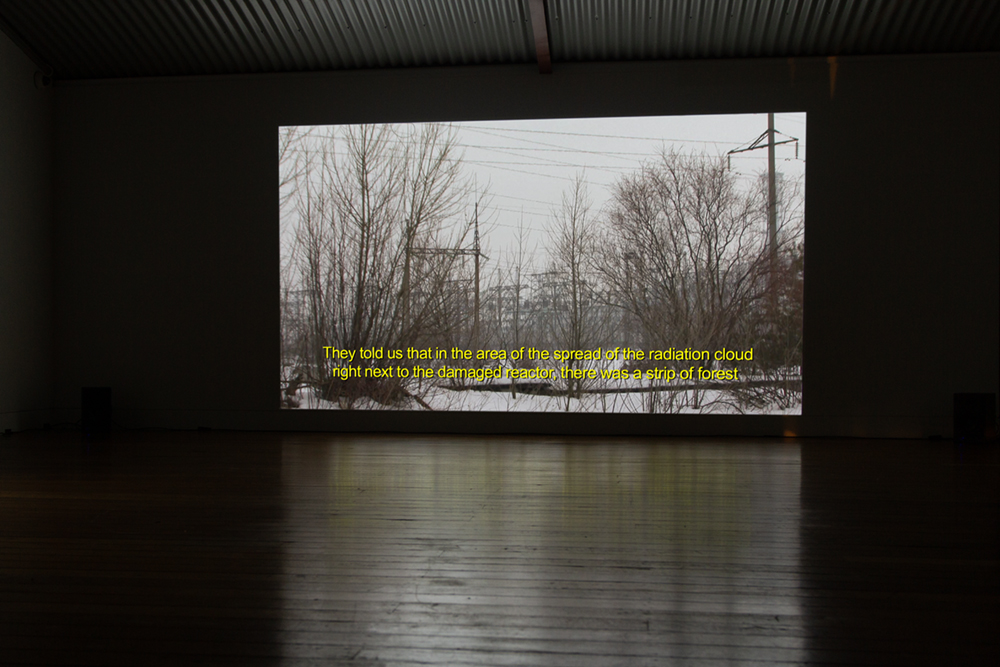

Precarious is a haunting evocation of the aftermath of the explosion at Chernobyl, 25 years on. This visually stunning road movie takes the spectator on a bleak journey from the shores of the Black Sea to the frozen heart of Chernobyl, passing through desolate, snowy landscapes, littered with abandoned villages. Squatting in this icy wasteland, the ghostly sarcophagus of Reactor No. 4 is a constant reminder of the threat still lurking below. Our companions are an unseen group of people who have experienced Chernobyl at first hand.

Precarious bears witness to both the folly and resilience of humans and to nature's fragility.

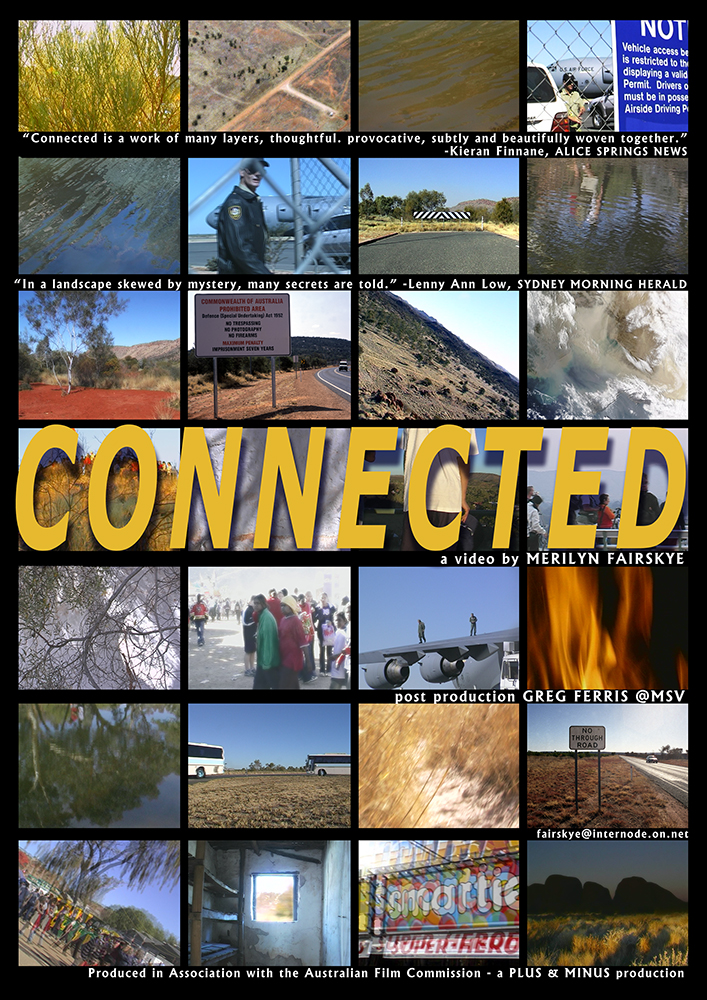

Merilyn Fairskye, 2003. Artist film. Duration: 21:00. Stereo sound. Three-channel video installation. Duration: 21:00. Surround sound.

Alice Springs is one of the most isolated towns in Australia. It hosts Pine Gap, a US-Australian Joint Defence Space Research facility, a base for global satellite technology and one of the largest ground control centres in the world. The base connects the world to Pine Gap, which plays a critical role in US nuclear command, control and intelligence.This work considers how disembodied and shadowy the experience of being constantly connected can be.

Connected trailer

Listen to "Red Forest"(excerpt)

Listen to "Heavy Water" (excerpt)

Encounter, imagine

The Cold War was my childhood, and we had pamphlets handed out in our street about what to do in a nuclear attack. Later, I lived in Darlinghurst, in the heart of the city, and down the street was a small, dank, photo studio that had been a nuclear bomb shelter. It looked just like the cage in Bunker 42, the once-secret nuclear command point in Moscow.

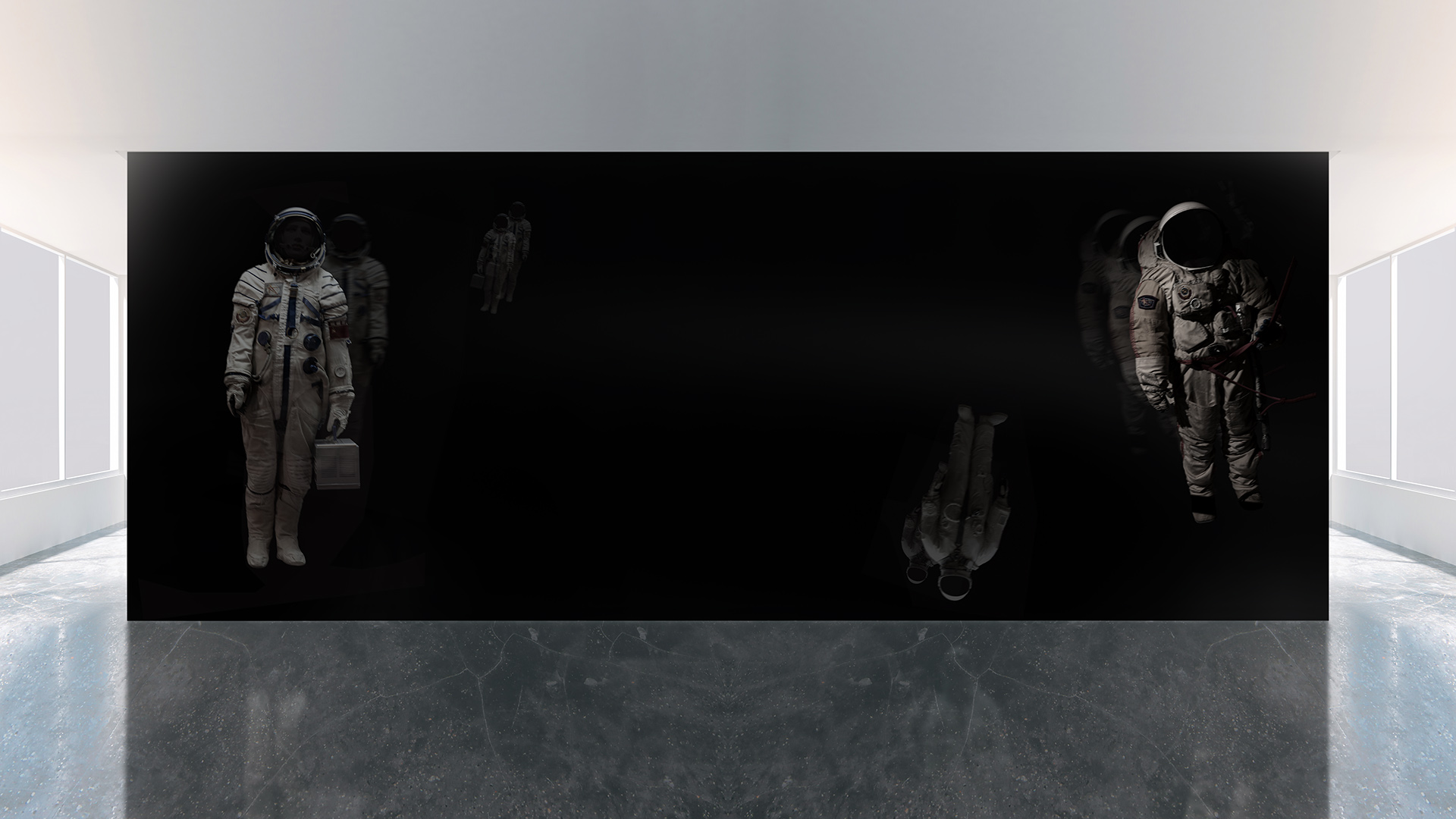

'Configurations' imagines futures for existing works, in new arrangements, but also, it creates possibilities for new work.

Empty spaces, public and private, set the context for the imaginary. Older works are transformed and new art emerges.

(Click on images to enlarge)

This place is not a place of honor.

No highly esteemed deed is commemorated here.

Nothing valued is here.

This place is a message and part of a system of messages.

Pay attention to it!

Sending this message was important to us.

We considered ourselves to be a powerful culture.

Nuclear Sites

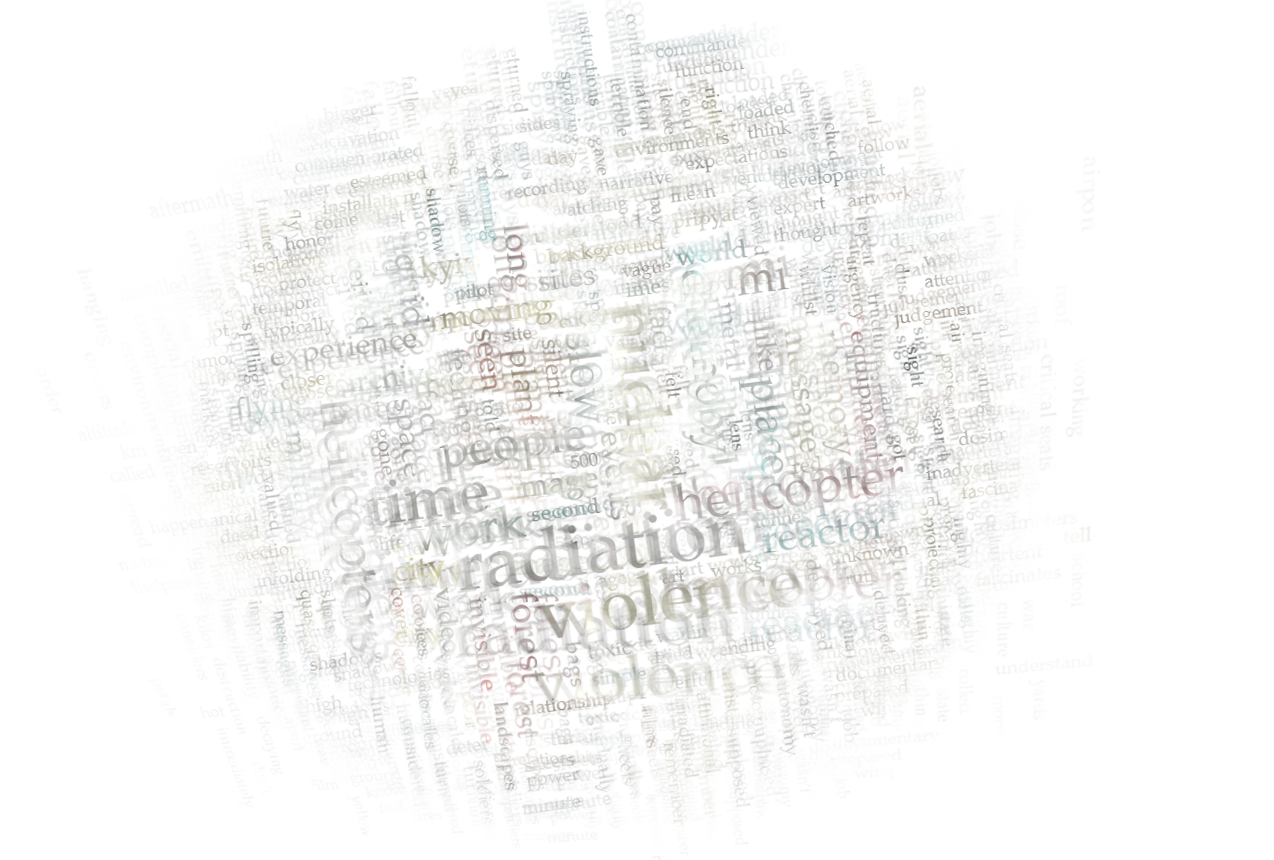

Why repeat the facts — they cover up our feelings. The development of these feelings, the spilling of these feelings past the facts, is what fascinates me. I try to find them, collect them, protect them. These people had already seen what for everyone else is still unknown. I felt like I was recording the future.

— Svetlana Alexievich ‘Voices From Chernobyl’

PeopleBy slow violence I mean a violence that occurs gradually and out of sight, a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all.

— Rob Nixon ‘Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor’

ResearchA shadow archive and an archive of shadows…

― Akira Mizuta Lippit ’Atomic Light’

ArchiveBeing there

Surrounded by secrecy, located in remote environments, vulnerable to weather, flawed protocols, political priorities, mismanagement and corruption, nuclear sites and locales are often beautiful, and always compromised.

In order to create visual encounters with the elusive and shadowy narratives embedded in nuclear landscapes it is necessary to be on location. Being there is to experience the unrepresentable.

Face to face

Many people shared their stories with me as I travelled to different nuclear sites to make art. They include Zoya lshkaryova, Oksana Khorozova, Oleg Khorozov, Igor Shchepotin, Yuriy Tatarchuk and Iuri Ursul from Ukraine; Yulia Semenova and Edward Samtzov from Kazakhstan; Martin Forwood and Janine Allis-Smith from the UK.

Theirs was lived experience, as the recipients of what had taken place, not the instigators. The human capacity to endure in the face of one of the central challenges of contemporary life - a workable coexistence between people, technology and the environment - creates hope and despair.

"That day, we started receiving calls to send away all foreign tourist groups. That is, our groups were not to proceed on their journeys - to Leningrad, Harkov, Almaty - we had to send them home immediately. We couldn't understand why this was happening. And then they called us and told us that there was an accident in Kyiv and all groups should be going home as soon as possible."

In 1986, ZOYA ISHKARYOVA worked at Intourist, Kyiv. She was interviewed in Kyiv in February 2010, by Merilyn Fairskye for Precarious. Translation: Ognian Pishev. (Edited)

I was going to work, because on that Sunday, I worked for Intourist. That day, we started receiving calls to send away all foreign tourist groups. That is, our groups were not to proceed on their journeys — to Leningrad, Harkov, Almaty. We had to send them home immediately. We couldn’t understand why this was happening.

You know, people at first tried to go somewhere, to change something in their lives. What can we do? We’ve got to live, adjust somehow. Our people were law-abiding citizens, they trusted the radio, television believed our government, and naturally, they were all waiting for an official statement, an official announcement that a tragedy took place and we all should leave Kyiv.

This is how it happened. What about our families? How did I send my son away? There were no tickets to anywhere, neither train nor airplane tickets. I simply approached the conductor, paid him some money, and sent him to very distant relatives in Askania Nova that I had never met because I only had relatives in Kyiv. This is where my son spent the summer.

There was no official information from our management – it was then the Intourist state company. We were only receiving requests from high-ranking officials to organize trips out of Kyiv for their children. What happened, how it happened, where it happened? We had no idea about anything. All those days from April 26 to, I believe, May 7, there were no official announcements.

On the radio and on TV we were beginning to get all kinds of information. First that we should take charcoal, then drink iodine. We took all kinds of things. Then another piece of advice was to drink red wine to wash out strontium.

Nobody ever ventured to tell us what happened, what tragedy, what catastrophe has occurred. If that cloud didn’t go over Sweden, we wouldn’t have known anything.

This is how we go on living— people are sick a lot more. Of course, we know why they are sicker. Many of them have problems with their skeletal system. Honestly, we don’t know what is happening in Chernobyl today. There is very little information.

"On the 1st of May, there was the parade. Nobody kept anybody away from that parade and because I was working at the Palace of Children and Youth, I was obliged to be there. At the time there were the Pioneers, I was with them, everybody was dressed in their Sunday best. Those were terrible moments, I will tell you honestly."

In 1986, OKSANA KHOROZOVA worked as a teacher at the Palace of Children and Youth, Kyiv. She was interviewed in Kyiv in February 2010, by Merilyn Fairskye for Precarious. Translation: Peter Kirievsky. (Edited)

What can I recall? That was a terrible period in the life of our country, especially the town of Kyiv and the Kiyv region. It was springtime, when the flowers were blooming. It was April, and you know, we didn’t know anything when it happened, on a Saturday evening when everybody was at home. Of course, nothing was said about this on the radio, and life went on. On that Sunday, I was working at the Palace of Children and Youth, with groups of children. So I came in to work around 10am, and our projectionist, looking worried, says, there is a terrible fire that they can’t put out. Near Pripyat, where Slavutich is.

This fire could not be put out for a very long time, but once again no one told us anything. I even remember that we went to a dacha the following day and walked in the forest. It was in a different direction, the Obukhov region, away from the place of the terrible accident. But radiation was flying all round. It is unseen. People didn’t know how to deal with it. You don’t see it, you don’t hear it, but it kills you and it sends the readings off the charts. Afterwards we all began to get information from one another. My friends would call me and say, Oksana you must leave, you must leave and take your kids away. At that time, I was 33, my son was 4, and my daughter was 10, so the children were small and had to be thought about. Any official I tuned to, or their friends, would say that everything was fine, they were saying, no, nothing’s wrong, just keep your windows closed. But the situation had been gradually building up because people on trams, on buses, would be talking between themselves, God, what is going to happen to us?

But on the 1st of May, there was the parade. Nobody warned us to stay away, and because I was working at the Palace of Children and Youth, I was obliged to be there. At the time there were the Pioneers, I was with them, everybody was dressed in their Sunday best. Those were terrible moments, I will tell you honestly. That was a moment even in the life of the entire planet, I’m not talking only about Ukraine or Russia, or other countries, for this was an explosion that changed life on the planet.

The collapse of the USSR followed soon after. This time bomb that was put in place in Chornobyl was slowly acting. It appears to me that it was all planned, not by us of course, but maybe the devil himself. I am religious, and I remember the words from the Bible about the Star of Polyn that will fall on the earth and that’s precisely what happened. How many people died, those firefighters, that’s so terrible. Helicopters were flying over our land, and were dropping down bags of earth, something like sand, it was all so insignificant and so laughable, when compared to the task of stopping this chain reaction.

The information was restricted, we did not know how many people had died, how many became ill, but a great part of the population unquestionably was affected in horrible ways. We were not allowed to leave work to pick up our kids and take them to some clean place. So, I sent my kids to my sister and I stayed here. You had to shower constantly and if you walked down the streets of Kyiv you had to throw away your shoes and your clothes. We didn’t know how radiation affects people. If we were able to see it or hold it or hide from it, but as it was, it was just everywhere.

From that terrible time, radiation for me is also connected with spring. All those flowers in bloom, the apple trees, the sky was blue. Such beauty around and death nearby. It’s very painful of course because at that time people were falling in love, getting married, life was going on, however, nearby there was death. And now it’s time to pray. So many misfortunes have fallen on Ukraine. I don’t want to distinguish Ukraine amongst other peoples and countries. Everyone was having it tough and yet Chornobyl is on our land. Again on our land, again, you ask yourself, after The Holodomor, those who have miraculously survived, then there was the war. And then seemingly peaceful times and yet another tragedy. How many boys, men, have died? What should we do? How can we move forward? When will this all end for us? Do we have hope of having a regular peaceful life, just living, going shopping, being happy, indulging in arts, literature?

Mankind must unquestionably learn from this. However, I will say, with some skepticism, that people don’t learn from other’s mistakes.

For the future people must protect themselves. It’s time to seriously think about ecology because we have no time left. Soon we might all die, because nature is screaming and begging, please save me, and we are just talking about it and not doing anything, and this is the main lesson. We must act to protect nature.

"We didn't seem to feel anything ourselves; those were relatively small doses, I mean in Kyiv which was a hundred kilometres from Chernobyl. On the other hand, there was the psychological and moral impact of the situation; first, because we didn't know how this will unfold; second, I can give you this example: after all the children had been evacuated from the city, only adults remained and it became a city without children. It had a huge psychological impact on all of us."

In 1986, OLEG KHOROZOV worked as a scientific engineer at the Institute of the Academy of Science, Kyiv. He was interviewed in Kyiv in February 2010, by Merilyn Fairskye for Precarious. Translation: Ognian Pishev. (Edited)

At the time I was a scientific engineer at the Institute of the Academy of Science. We knew about the creation of the nuclear bomb, of the tests that took place in Russia. We knew that there were people there, people who survived. Then all the dangers and memories of Hiroshima and Nagasaki – the consequences of such an explosion – we were really scared and afraid of looking at it, because it was so hard for us to comprehend.

We didn’t seem to feel anything ourselves; those were relatively small doses. On the other hand, there was the psychological and moral impact of the situation. First, because we didn’t know how this will unfold. Second, I can give you this example: after all the children had been evacuated from the city only adults remained and it became a city without children. It had a huge psychological impact on all of us. A strange city with no children, only adults moving around – it was like being in an unpleasant science fiction movie.

Overall, there was no discernible impact on people’s health; I am saying again – those were small doses. However, there was constant stress. You could get gamma radiation on your clothes or be exposed to beta radiation – if your shoe went into a puddle, or mud – and then we had to throw them out. This was based on science. Very few people knew that we had to throw out those shoes, those clothes. People were busy trying to launder their clothes and naturally this couldn’t change anything. There were all kind of recommendations but being the first ones, they were not based on methodology, nobody knew what recommendations should have been issued, how we had to behave. We washed windows, closed the window shutters; whether this helped or not – nobody knows. Especially when the incidence of low-level radiation is only felt after 20-30 years, and you need statistical data to discern the tendencies.

Geographically, Chernobyl is on the Pripyat River, which flows into the Kyiv Reservoir and further down into the Dnieper River and then flows through the whole of Ukraine. We started creating models, computations of how these water flows would proceed, where would all this water go, because, contaminated water was going from Pripyat, through the Kyiv Sea and the Dnieper River. We needed to analyse the level of contamination, to find out how deleterious the doses were; how this water would spread all over Ukraine and what had to be done to try to stop this process. It turned out that reality was quite different: the Kyiv Sea is quite shallow and spread over a large territory – and there are roads on that land. One of those roads, we later called the “Road of Life".Regarding Chernobyl, we should be grateful that we had this natural defense – the Kyiv Reservoir. If it weren’t there, or the nuclear plant had been built in the wrong location, the first blast would have contaminated half of Ukraine. It would have been hit by those radioactive nuclides. Everything happened by chance. But these technology catastrophes should be anticipated, people should be forewarned and prepared to meet them.

"You are seeing in front of you a man who during that time was living in Kyiv, worked in this institute (the National Cancer Institute), and here in the ward next door we were admitting the firemen who absorbed the first blow. Those were young guys who directly took part in putting down the fires at the plant, they arrived with the same working clothes they were wearing. Using the regular Geiger counters did not make sense, they were not ticking - tick-tick-tick - they were singing such songs that it was scary"

In 1986, DR IGOR SCHEPOTIN was an oncologist at the National Cancer Institute, Kyiv. He was interviewed in Kyiv in February 2010, by Merilyn Fairskye for Precarious. Translation: Ognian Pishev. (Edited)

Traditionally in Ukraine we observe higher levels of cancers in the eastern and southern regions, while they are much lower than the average for the country in the West and North. The increase begins after 25 years. That is why we expect an increase in cancer disease to start in 2011, some time next year.

We can only assess the population living in the exclusion zones or neighbouring the Chernobyl power plant zones. However hundreds of thousands of people from all parts of the Soviet Union were mobilized for the elimination of the consequences of the disaster. They would work together in the same place – I can’t recall how long was their shift – something like 3 weeks – and then they would immediately go home to all other regions of the Soviet Union.

I was living in Kyiv, working in this institute, and here in the ward next door we were admitting the firemen who absorbed the first blow. Those were young guys who directly took part in putting down the fires at the plant…they arrived with the same working clothes they were wearing. Using the regular Geiger counters did not make sense, they were not ticking – tick-tick-tick – they were singing such songs that it was scary.

Why am I saying this? Nobody around me registered the level of radiation, neither among my colleagues nor among the majority of the population in the country. This was done, to a certain extent, partially, for the people who were working on the site directly. And even their level of radiation was not known to them since those were secret data.

Young guys – 19, 20, 25 years old. They were all strong, healthy kids, irradiated. They were brought by bus and we placed them on the top floor. You can imagine, the Cancer Institute, operations going on, the place is full of patients with severe cases of cancer – and on the last floor these young kids who didn’t understand why they were here, what happened to them. And so evening came, the weather was beautiful, the sun shining, no rain, the clouds dispersed, warm, beautiful weather and they sit and play guitars, sing songs, drink vodka, and people in enclosures like birds. And we were monitoring them: every couple of days we would move three or four people into intensive care, then another three or four, and they all quietly disappeared from life.

The people who were affected by radiation, they are younger, they have smaller tumours, they metastase much quicker and there is a much higher incidence of lethal outcome after surgery. We were seeing differences between the development of the disease in this category of patients and those who haven’t been affected by the Chernobyl catastrophe. Even in the presence of very small tumours, those tumours metastasized faster than usual. And unfortunately, among those cancer patients, we encounter a much higher statistically significant number of post-operative complications, higher that the world or the Ukrainian average.

From my point of view, the Chernobyl catastrophe had a number of consequences for the lives of people in Ukraine. And this is not only the direct impact of the disaster as such and the health of people. After the accident there was a dramatic drop in birth rates. And now, next year, for example, it is the kids born in 1986 that enroll in university. We are already suffering from a deficit of future professionals. We can now say that because of this demographic “hole” we will face a moment in the near future, when retirees living in this country will stop being supported adequately by the children of the Chernobyl generation.

I am talking about a narrow perspective, however, we can say that the Chernobyl disaster led to an increase in psychiatric disease, in psychosis. Normal people all started to be affected by psychoses on the topic of Chernobyl, radiation and so on. The problem is that from this region – at that time I was living in Kyiv – I remember acutely well what was happening; when children left the city en masse, all the women left the city; when Kyiv, this huge megapolis was inhabited by men only. And since there were threats to their health, men were leading a particular way of life. It is because the use of alcohol was recommended as protection against radiation.

This disaster created a huge lump of problems – not only through its direct impact on the worsening health condition of the population, but it also had secondary, tertiary consequences. We are not fully aware of all the incidences of this catastrophe; I think that we are standing on the threshold of the realistic evaluation of this horror that befell on our country.

"Right now it's a really interesting job for me and if for example twenty years ago somebody should tell me that I will work in Chernobyl I should laugh of course. I never planned to do that. I remember the first time when after university I went to work in a school for a Slavutich company set in Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant - I was a school teacher then. So, I didn't plan to come here."

In 2010, YURIY TATARCHUK was Deputy Head, International Department Chernobylinterinform, Chernobyl. He was interviewed in Kyiv in February 2010, by Merilyn Fairskye for Precarious. Translation: Ognian Pishev. (Edited)

Twelve years ago, I was just curious when I was invited to work here, I was curious as to how it looks like - Pripyat town - I wanted to investigate it myself, and I thought maybe for a couple of years, I would work here, and it would be enough for me, but now for me its ordinary work on one side and on the other side we know how to manage the situation when we are on the contaminated areas and how to protect ourselves.

One of the first things that really impressed me is the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant and Chernobyl town are two different places. The distance is 18 kilometres between them. I didn’t realise it. Because the character of contamination at first wasn’t clear, that’s why, according to the radiation safety notes of those times, all people were resettled from the distance of thirty kilometres. With that background the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone was established.

So, in modern times, there are two main directions of human activities there. One is the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant (CNPP), and its transformation into an ecologically safe object, and taking care of the Exclusion Zone. The main task of all this activity is to protect territories of Ukraine and all over the world from extra pollution and contamination outside. Sure, most important is Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. First of all, it’s necessary to solve the problem of spent fuel, which is still inside the CNPP. It’s necessary to construct the next Confinement over the existing object shelter, erected at No.4 where the accident was. There are 4,000 people responsible for that; they are employed for the CNPP. The same number of people work in the Exclusion Zone. There are 4,000 people, nine companies, and their general task is to mitigate consequences of the accident of 1986, and to minimise migration of radioactivity outside of the Exclusion Zone.

Ukraine has a very complicated economic situation. So, to find a job elsewhere is very complicated, especially for people who live in Slavutych because there are no choices of jobs there. This town was constructed especially for CNNP. There are no other industries there. Unfortunately, salaries are not too high, especially in Chernobyl. In CNPP they’ve got another range of salaries. In the Exclusion Zone it’s not a lot. According to the legislation people who work inside of the Exclusion Zone, and in such period of time, it’s about seven years, they have rights, they have the possibility to retire earlier, for men it’s fifty years and for women forty-five years old. Sure, there are a lot of limitations. It's not like in other places. There are no under-18-year-olds – they are not allowed here. That’s why people stay here without families. And also, it’s not allowed to consume alcohol before 7pm.

So nowadays Chernobyl exists like a shift settlement of Exclusion Zone, and the same time an industrial zone for the Exclusion Zone too, because all companies are concentrated here in Chernobyl. That’s why it doesn’t look abandoned. So, people walk around, but all of them are employees of the Exclusion Zone.

All objects that are constructed for the decommission of the CNPP have a lot of delays. As for construction of the New Confinement, I hope it will be constructed very soon. But there are hundreds of tonnes I think of very radioactive materials. To leave it as one accumulation, who knows how dangerous this would be. To manipulate it, to start to reload it, where to bury all of that, how big a disposal unit should there be for that.

For Reactor units 1,2, 3 and 4 they used this cooling system. There is a cooling channel which after that flows to a cooling pond, an artificial lake constructed for the Nuclear Power Plant. But there were some mistakes in the projection of the pond because the calculation was done for 12 reactor units. There are 22 square km of the lake but it wasn’t enough for Reactor Units No.5 and 6. That’s why there were extra cooling towers constructed for them.

There is a disposal for spent fuel for the Nuclear Power Plant, but the French company which was responsible for construction of it, who got this contract, they made a lot of mistakes in the project. So in 2003 when it was supposed to be commissioned, and should be possible to start reloading spent fuel from the NPP to it for long term disposal, the International Commission didn’t accept this object.

Some people go here, because they need to, especially people who live in the neighbourhood of the Exclusion Zone. They are mostly people who live in the villages, farmers, and right now, unfortunately, there’s the famine. It’s very complicated in Ukraine and people almost joke because we had collective farms before and right now all of it doesn’t exist anymore. That’s why people are jobless, and that’s why, just to feed their family they go inside, for fishing, hunting, to sell that off, and, for example, to collect scrap metal.

I am an inhabitant of the Soviet Union. I remember those times. That’s why for me, I have a completely different attitude compared with Western Europeans because for them in Soviet times, we were, the Soviet Union was, the enemy. Right now, it’s like a destroyed empire of evil, like somebody named it in this place. So, for them it’s interesting to have a look at what they were afraid of. It’s like to overtake the phobias of the past. For some of them. And for us, sometimes we have a nostalgia to go back to the Soviet time because when we come back to Pripyat town when we visit some buildings, especially schools, we are very emotional because it’s like travelling back to childhood.

It should be very useful for people to visit this place and to see everything, understand everything from their own experience because reports sometime, reporters, filmmakers, they pretty much exaggerate the situation, what’s going on. Actually, I think we don’t have a word to name Chernobyl and all of this Exclusion Zone, because it’s something like reality on the one hand and from another hand something surrealistic. I mean, all this Exclusion Zone – so on the one hand it’s a museum, like a memorial place of those times, from another hand it’s an industrial zone, so...it’s something abnormal, I think.

"I am a liquidator of the aftermath of the catastrophe at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. I worked there in May 1986 as a commander of an MI-2 helicopter. How did I get to be in Chernobyl? The commander of the flight wing called all the crews to the navigation centre and informed us that several helicopters were needed to work at the site of the Chernobyl nuclear plant on the liquidation of the aftermath of the accident."

In 1986, IURI URSUL was a helicopter pilot with the Uzhgorod United Wing. He was interviewed in Sydney in July, 2010, by Merilyn Fairskye for Precarious. Translation: Ognian Pishev. (Edited)

My name is Yuri Ursul. I am a liquidator of the aftermath of the catastrophe at the Chernobyl nuclear plant. I worked there in May 1986 as a commander of an MI-2 helicopter. How did I get to be in Chernobyl? In April-May 1986, I was working as a member of the group that carried out aero-chemical work in the Kyiv region from the Uzhgorod United Wing (Avia detachment). I was employed in Uzhgorod but we were sent to Kyiv where there was a deficit of pilots and helicopters.

I first heard about the accident in Chernobyl when I went to Kyiv for May Day. Although I was working in Uzhgorod, my family were living in Kyiv. So I flew to Kyiv to be with them during the weekend. I went to the parade with my daughter, walked in the streets. It was beautiful sunny weather. I remember as though it is today: an international cycling competition was taking place – we stood for a while along the route, watching. We were in excellent spirits but I was already hearing conversations in the crowd that an accident had taken place. As a civilian not versed in the details, all the nuances, I did not understand the dangers, what it was, what radiation was. It doesn’t have colour, smell and we didn’t really feel it.

Later, after the public holidays, I flew back to my work. Up in the air I received the order from the air traffic controller of Juliany airport to return to the base ASAP. I flew to the base, gathered my crew – I had a navigator-mechanic, an aviation technician – and we flew to Juliany airport. And upon arrival I immediately sensed that something must have happened that was quite out of the ordinary, something very serious.

The entire square in front of the airport was crowded with black cars, mostly Volgas, and there were lots of respectable men who were using all possible means, legal and illegal, to pass through the checkpoint or through any available gates into the service area to get on a flight out. There were a lot of flights, most of them to Moscow or south to Crimea. Later, I learned that practically all high-ranking officials of the city of Kyiv who had access to more information than we simple mortals, were sending away their families, their wives, children, as far away as possible. And at the same time, with a nice smile, they were telling us that nothing really dangerous had happened, everything was normal.

Upon arrival at Juliany airport, the commander of the flight wing called all crews to the navigation centre and informed us that several helicopters were needed to work at the site of the Chernobyl Nuclear Plant on the liquidation of the aftermath of the accident. There was a need for experienced crews and in general we had the honour, this is how the whole issue was presented, that it was a real honour.

So how come I got to be one of them? It is worth saying that they had a young pilot from Uzhgorod for this job, whose work experience was just 2 or 3 years. And he told us later, his mother forbade him to participate: he had a fiancée, he was planning to get married, he didn’t have any children yet. Obviously, he had understood that this was something really serious.

In general the choice was: either I fly, or if I decline to fly they will have to call on some other pilot from Uzhgorod, because there was a distribution list, and two helicopters were required with crews from Uzhgorod. I understood that basically there wasn’t much of a choice – if I didn’t fly, someone else from the guys would and it didn’t make sense to refuse. For ethical reasons I couldn’t do that. There were no heroics, no desire to show off. Simply, we were educated to be like this. I served in the military, and I knew that an order was an order. That is why they didn’t give us the time to go home say goodbye to our families, they immediately issued the flight instructions and told us to fly to Chernobyl where they would explain everything to us. A change of clothes and everything else that we might need to carry out our work would be waiting for us. It is worth mentioning that the accident took place in the town of Pripyat. The Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant was named after the nearest locality which has a more ancient history — Chernobyl. That is why we didn’t fly into Pripyat, the town that had already been evacuated and was without a living soul in it.

We flew into Chernobyl where the base was – a military unit was deployed there, there were military helicopters, there were several generals — the top brass. The atmosphere was such that immediately upon arrival we plunged into a war situation; everything was very strict, no smiling faces, everybody doing his job and tension floating in the air.

We were invited to equip our helicopters with protection against radiation. What did they offer us? There were piles of bags full of shots. My understanding was that they had come from a hunting shop; there were even marked accordingly — they were in bags weighing some 5 kilos each. Since the lead shots were quite heavy they were distributed in small bags. Also there were these sheets, I can’t even tell what material they were made of but it wasn’t steel, it was something soft that you could cut with iron. We had metal scissors which could cut that metal. My technician and I cut chunks of these sheets and laid them in the cabin around our seats and on the floor, the sides, the blisters. We covered everything with these pieces of metal. And those bags with the shots, we put them under the seats so that they would shield us from radiation.

Our two MI-2 helicopters were working. There were military helicopters MI-8, MI-26 and I think there were also military helicopters MI-28. These are machines for battle support. What function did they fulfill? I don’t know. They were most likely used for aerial photography. They were equipped with sophisticated video-cameras.

When our helicopters were ready we received direct instructions regarding the job. The task was this: scientists had developed a liquid which, when sprayed, turned into a thin film in contact with the air. And they told us that around the spread of the radiation cloud, right next to the damaged reactor, there was a strip of forest which people called the Red Forest. Because it was May, everything was green, beautiful and this forest was truly red. One had the impression of deep autumn. Tree leaves had turned yellow, red, after the ejection of radiation. The Red Forest was emitting very strong background radiation and we had to somehow deactivate, neutralize it.

Since our helicopters had equipment installed for aerial pesticides, it was decided to modify the equipment. Instead of fertilizer they pumped this particular liquid into our reservoirs. On both sides there were pipes which were used to spray this liquid. We had to fly over the forest at a 30-50 metres altitude, then switch on the equipment and start spraying the liquid, which was supposed to turn into a thin film and cover the forest.

We in general were prepared for this type of work because we did similar jobs so many times. The only thing that we were told sotto voce was to fly as close as possible to the ground while we were performing our jobs. Of course, it doesn’t make sense to maintain a 30-metre altitude.

Of course, we tried very hard. Our wheels almost touched the cones of the trees. Only now do I understand that this wasn’t a smart idea because the background radiation was extremely dangerous. They gave us dosimeters which had an accumulative function and sent us to work there. And the dosimeters were expected to last for 2-3 weeks.

They were replaced at the end of every day. I learned that the last reading on my dosimeter was 47 Roentgen, and the background radiation was three times bigger than the maximum admissible dose that is permitted for pilots. I had to return several of those dosimeters. You can only imagine what dose of radiation we got there.

In parallel with us, work was conducted by the military helicopter pilots. I am certain that they were the guys who were flying MI-8 military helicopters. They would be hanging above the nuclear reactor to measure radiation levels directly from the muzzle of the reactor that was still breathing, from the destroyed reactor. They hovered above the reactor at some 100 metres, and lowered the measuring equipment into the hole on a long rope. I don’t think any of these guys are still alive. They were all declared “Heroes”, they all received medals. This intense terrible background radiation from the destroyed reactor didn’t spare anyone.

Once I had to work with a TV crew. I had two people on my helicopter, a journalist and a cameraman, and for an hour and a half we flew over the destroyed reactor, and over the city of Pripyat, and they were filming with the video camera reporting from the site on what was happening at the nuclear power plant and in the city of Pripyat.

I have got to tell you that my feelings were not pleasant ones. First of all I already understood that radiation is something terrible, unexplainable, and at the same time I had the feeling that the reactor which was still glowing, was emitting rays of light from the molten metal. And when I saw the soldiers running on the roof of the reactor in uniforms with some fake protection, normal people — soldiers, running on the roof throwing pieces down with some metallic pincers — I already understood that all those guys were sentenced to death. Those were people condemned because the level of radiation was so high, even at the altitude at which we were flying.

The city of Pripyat was in the immediate vicinity of the destroyed nuclear plant. It was completely empty, dead. I had an eerie feeling – there was laundry hanging in the yards, on the balconies, you could see cats and dogs running in the street. Why am I saying this? Because were flying low and you could discern all these details. There were balloons flying in the air. That is, the feeling was that people were about to appear out of their apartments, but we couldn’t see anyone. And this all made me feel cold in my stomach.

I am talking about the impressions I had at that time. We were completely absorbed by our work and we were trying hard to do it as best as we could because we were told that a lot depended on it, including the fate of the city of Kyiv. If we could not do our work they would have had to evacuate the entire city of Kyiv. And this is not Pripyat. This is several million inhabitants.

After we received the orders in Chernobyl, we received the materials and equipment, special white clothes, pants, jackets, all white, caps, they gave us what we called “petals” something that prevented dust from entering our throats; helicopters take off and land and there is a lot of dust at the airport. They gave us these gauze masks and they advised us never to take them off and to wear them all the time. I tried of course to follow these instructions and it was hard – it was really hot, stifling, it was hard to breathe. Those petals were quickly saturated with dust. However we all understood the existing danger and we tried to follow orders.

The helicopter had protection installed; I had loaded a lot of useless metal. And in reality, whenever I loaded the 500 kilos of that liquid into the cisterns, given the hot weather and lack of winds, the helicopter was working at the limit of its capabilities. During takeoffs I would break into sweat because the machine could fall at any time. It was a vertical takeoff. There was the moment when the helicopter was supposed to hang and then start the forward horizontal movement. At the moment when I pushed the handle away from me, the helicopter would sink and my wheels practically touched the ground. At that point I felt that I could simply hit the ground and turn over. Tension was running high, incredibly high. But at the same time, God spared my life. I was lucky, every time I managed to take off with all this excess weight, and then go on my assignment, spread the liquid and come back.

On the second or third day, they assigned the same job to another helicopter – the MI 26, which is, if you know those helicopters, the biggest helicopter in the world. The MI 26 can lift over 26 tonnes. They had some special reservoirs which were used to fight forest fires. Those helicopters had just returned from France where they worked on forest fires. This time, the reservoirs were not filled with water but with the same liquid that we also carried. Unlike my little helicopter which could only take 500 litres max, that helicopter could take 20 tonnes. We did the maths, we would see that it was 40 times bigger. You understand that the efficiency of its work was 40 times greater. And also if we compared the cruise speed of my helicopter and the MI 26. I was flying at 150-170 km/h, those helicopters were flying at 250-300 km/h. We were almost getting in the way.

We spent nights in the city of Chernigov. This is a city east of Chernobyl, not far, at least much closer than Kyiv to Chernobyl. In Chernigov they had an aviation school and they prepared a field airstrip for us at the base of that school. Every day at the end of work in Chernobyl, at sunset, we returned to Chernigov to that military airfield and we parked the helicopters in a well-defined order and they were immediately deactivated in a most thorough way. There were water trucks – they would arrive immediately and start spraying the helicopter with some deactivation liquid.

We would take off our white overalls to be washed, we took off shoes, everything. The tents were right there where we had showers, we also underwent deactivation. And then we went to the hotel to sleep. We slept together with the military pilots.

When we finished that work we received the order to go back to Kyiv. I went to Kyiv to my family. I remember my state very clearly – so many years have gone by – but that state I remember minute by minute. I had come back from a war, we did feel that we were fighting a war. And suddenly, having flown back, left the airport, approached the trolley bus, got on to travel to downtown Kyiv, I understood that I was in a completely different world.

The feeling was of elation because the chestnut trees were flowering in Kyiv, birds were singing, the atmosphere was carefree and the fact that we returned from “there” was a miracle. I probably will remember all my life this internal state of mine when I saw for the first time the nuclear reactor from the air, the destroyed nuclear power unit which was still reeking, still alight, and the city of Pripyat. After that, after that, when I got home I saw this carefree beloved Kyiv. These are the two feelings that have been etched forever in my memory.

In 1987 or 1988, I don’t remember exactly, we were given medals. I got the “Badge of Honour.” My colleagues — some got the medal of the October Revolution, others — the medal of the Red Flag, there were even “Heroes of the Soviet Union”.

But I think that nothing could compensate for the loss of health that we experienced. As time went by, my health was getting worse, even though my professional career was on the ascendancy, I had to think seriously about my health and we decided to emigrate to Israel. At least because medicine is well developed in Israel and the climate, the abundance of fruit, vegetable, all this helped me recover. We lived in Israel 5 years, and I began to recover the good health that had been given to me by nature (before Iuri moved with his family to Australia to live).

At home – in Russia, Ukraine and Belarus, thousands of Chernobyl people are leading half-starved impoverished lives because there is no medical care, which still existed during the first years, in the Soviet Union. One could be admitted to hospital, have a medical examination. Now this has come to nought. In practice there are kopecks, ridiculously small amounts of money, there is no material support, none of the promises to provide housing. They delivered all those medals and official citations, thanked the people and forgot about them.

That is why, even the fact that people in Australia are interested in Chernobyl, and I have been invited to share my memories and impressions, this all shows that people are not indifferent to what was happening with me, what was happening in our country. I want to talk about it, because I know that hundreds, maybe thousands of my colleagues – pilots, mechanics, or simply regular soldiers – who worked there, are no longer alive.

I would like very much to end on an optimistic note, that the memory that is being brought to light will help people be closer to each other and not allow those errors, those tragedies that occurred in April-May 1986 in Ukraine to happen again.

Janine : "I knew nothing about Sellafield and when my sons were little we used to take them regularly to the beach. When my eldest son was twelve he developed leukaemia and this was just after there had been a documentary about the high number of children who developed leukaemia around the plant."

Martin :"They found radioactive swallow droppings in the buildings, and you think, these poor birds have flown whatever it is, 3000 miles from Africa somewhere, to come to Sellafield, they become contaminated, they fly home again, and there's no knowing exactly what effect that has on their offspring."

JANINE ALLIS-SMITH is an anti-nuclear campaigner who, with her late partner and fellow campaigner MARTIN FORWOOD, founded C.O.R.E. (Cumbrians Opposed to a Radioactive Environment) . She and Martin talked with Merilyn Fairskye in October, 2015. The film BIRDS is dedicated to them. (Veteran Cumbria anti-nuclear activists recognised with Nuclear-Free Future Award)

Living in Cumbria I think my main worry is the children in the area. I knew nothing about Sellafield (insert link here) and when my sons were little we used to take them regularly to the beach and when my eldest son was twelve he developed leukaemia. This was just after there had been a documentary about the high number of children who developed leukaemia around the plant and of course people were asking questions but the plant always denied that their discharges of radioactivity had anything to do with it, and people didn’t believe them. They felt that having taken their children to the beaches, once they developed leukaemia that Sellafield had something to do with it. So ever since then, my son was lucky, he survived, but some of the other children died, and we’ve never had any answers. The plant, Sellafield, denies that their discharges were ever high enough to cause the leukaemias, but we do not believe that they were ever totally honest about the discharges or that they can ever precisely admit how much was discharged.

There's been accidents, e.g. the Windscale fire where it spewed out radioactivity over the county for days before people were even warned to keep their children inside or not drink the milk and I think that even as a result of Sellafield’s normal discharges the environment we live in has become radioactive. To totally dismiss the belief that some people have that their radiation does cause leukaemia is wrong. Take the dirtiest plant in the world with the highest discharges, you then have the highest incidences of leukaemia and to us, you don’t need to be an Einstein to connect it, particularly when one of the only known causes of childhood leukaemia is radiation.

So we’ve never believed them when they’ve said, Well, it’s nothing to do with us, it’s because people come in from outside, it’s an unknown virus. To date, this unknown virus has never been identified, nor has there ever been an antibody to it been found in children with leukaemia.

But here in the UK it’s the only country that really pushes population mixing as a cause of leukaemias, and as far as we are concerned, the jury is still out. Research is going on but sometimes we feel that even those scientists who are supposed to be on our side, they have come from the nuclear industry and they are more gatekeepers for the industry than being bothered about whether or not they have actually caused the leukaemias and until somebody stands up and independent research is done, and I don’t think it will happen just yet, but it will come eventually.

There’s a lot known about Sellafield, particularly the operations it carries out, the accidents it’s had over the years, the contamination of the local environment. But there are also some other strange stories that have arisen over the years, and perhaps one of the strangest is about a local flock of feral pigeons.

In the local village next door to Sellafield, there were two ladies who treated these pigeons as their family, and it must have been a flock of several thousand used to congregate on their house’s roof every day and the ladies fed them and cossetted them and helped them when they were sick and so on. What people didn’t realize was that at night those pigeons were leaving the village and flying back to Sellafield where they would roost in what were clearly nice, warm, cosy, unknown to them, radioactive buildings.

And it got to a stage at one point where the flock got so big that the neighbours of these two ladies, who run a guesthouse, complained about the mess the pigeons were making. So it was decided to cull some of the pigeons to reduce the numbers. But it was pointed out to them that before you cull them, make sure, you know, are these pigeons radioactive or not because they spend every night at Sellafield.

So, an investigation was done, samples were taken, and the levels of radioactivity both on the surface of the birds, on their wings and feathers and so on and internally, were really high, exceptionally high levels of radiation. And when that was discovered it prompted what was then the Ministry of Agriculture to issue a public warning that people were not to come in contact with these birds, they were not to kill them, they were not to try and eat them and so on, those pigeons were taboo from that moment onwards. And in the end the whole flock, over 2000 birds, were culled.

The following problem was that having 2000-odd dead pigeons, where do you put them? In fact, it actually created for the industry a fourth level of nuclear waste – you had low-level waste, intermediate-level waste, high-level waste, and then you had flying waste which is the way people looked at it then. And the problem was, where do you put radioactive pigeons? You can’t just throw them out in with the rubbish in the local bin collection. And in the end, they had to be buried in lead canisters in the National Low Level Waste Dump, that’s how radioactive they were. And if these two dear ladies thought that was the end of their problem, they had another thing coming because somebody then realized that if the pigeons were radioactive the droppings would have been radioactive and the ladies’ garden would have been radioactive as well. So, they had to completely excavate the top layer of the garden. The whole lot was simply dug up, removed and also buried in the National Low Level Waste Dump at Drigg, just south of Sellafield.

People visiting the area, you might see a pigeon flying around, you never would have believed in a million years that they could be very, very radioactive. And it's just another sign of how dangerous this industry can be, not just from the conventional dangers of accidents but from birds flying around. The same thing has happened over the years to swallows that visit the site. They found radioactive swallow droppings in the buildings, and you think, these poor birds have flown whatever it is, 3000 miles from Africa somewhere, to come to Sellafield, they become contaminated, they fly home again, and there's no knowing exactly what effect that has on their offspring. Will their offspring be radioactive?

Sellafield also hosts a number of open storage ponds that have been there since the 1950's, the 1960's, and the water is highly radioactive on these ponds, and of course it's an absolute haven for the local sea gulls, who like to swim on them. So where you've got Sellafield you've got this sort of magnet that attracts other birds and animals, for that matter, and coming into contact with the place simply ends up with their getting a hefty dose of radiation. And it's something that most people would not associate with Sellafield - somehow this connection between wildlife and what goes on at this grotesque nuclear facility on the West Cumbrian coast.

There's a sad ending to story of the pigeon ladies. There was a horrific event some years ago where a mad gunman went on a rampage and shot a number of people, I forget how many, it was ten, fourteen, something like that, and one of them happened to be one of the pigeon ladies who was just walking in the local village, I think distributing catalogues of some kind, and she was randomly shot. And the guy's name was Derrick Bird. It captured international headlines, this mass shooting of innocent people.

"We never actually heard the explosions, because the test site was located 150 kilometres away from Semipalatinsk. But we felt a small earthquake, which happened every Saturday morning, sometimes another day of the week..., the floor, the walls, the furniture in the room, were trembling. It wasn't frightening at all. It was so common for me."

YULIA SEMENOVA, academic, was interviewed in Semey, Kazakhstan, in May 2015, by Merilyn Fairskye, (Edited)

My name is Yulia Semenova, I work at Semey Medical University as Associate Professor. I was four-years old when my family came here from Vladivostock to Semipalatinsk in 1967, as my father had a professorial appointment at the university. All my life, I experienced living near the nuclear test site.

We never actually heard the explosions, because the test site was located a hundred and fifty kilometres away from Semipalatinsk. But we felt a small earthquake, which usually happened every Saturday morning. So, the floor, the walls, the furniture, was trembling. It wasn't frightening at all. It was so common for me. At that time, I didn't know anything about the adverse effects of nuclear tests. We didn't really discuss this within the family or with my classmates or with my friends. First, it was prohibited to speak about that and second, we didn't feel that there was something special about these earthquakes. It was just a part of our life and that's it.

The situation changed in the late 80s, early 90s, when the Soviet Union broke down. Information became available to the public and it was OK for us to have some discussion. And there was a big antinuclear movement called Nevada Semipalatinsk, and it was frequently discussed in public. We looked at how these nuclear tests had a lot of side effects, and that it's a part of the Soviet military system that we were sort of experimental animals for. Not those who lived in the city, but those who lived closer to the nuclear test site They were periodically checked and their dosimetry records were kept. So, we're used for the purposes of research. I was 18 years old at that time and it was the first time that we were discussing these nuclear tests.

So, when I was a medical student and the nuclear test site was closed, the president signed his first decree - to close the nuclear test site. It was widely discussed in our media. We saw a lot of people who were born during the nuclear explosions, people who had severe congenital anomalies, who were seriously ill, and at that time, we all believed that we are contaminated, and that we are going to have a lot of health issues, maybe not now but sometime later. But as I matured as a medical professional, I learnt a lot about international studies at the nuclear test site. There were many researchers from Japan, from the USA, who did detailed health research that showed that the only disease which actually increased in prevalence due to nuclear tests was thyroid cancer. Other disorders were not specific to the test site. So nowadays we should not speak about medical or health effects, we should rather speak about psychological effects. Local people still believe that they are affected due to the nuclear test site. We call it radiophobia. There was other research that showed that the anxiety and depression rates in populations, especially in the population living in the villages surrounding nuclear sites, is higher than in the population living in other parts of Kazakhstan. Even medical professionals who live in other parts of Kazakhstan, for example in Western Kazakhstan, Central, Southern Kazakhstan – although they have knowledge of health effects – even they often believe that we are being exposed, we are being contaminated.

From one side, it’s ridiculous and I laugh, but from the other side you feel yourself victimised. So it’s rather humiliating. So, although I laugh when I hear things like this, inside I don’t feel really comfortable.

Our country’s officials, the authorities, want us to forget about the nuclear test site and it was one of the reasons why the city changed its name from Semipalatinsk to Semey so that nobody will attribute the place to the nuclear test site. We are a different place now; we are no longer about the nuclear test site. And local people don’t really like that the officials try to make us forget about our past because we still believe that this damage was not adequately compensated. We still want the problems that we face to be discussed, maybe we want to have some additional health benefits or other benefits paid by the government. The present situation is that “forget about the past and look into the future” which is not related to the former nuclear test site at all. So, pretend that it doesn’t exist, that it never existed before.

If you talk to somebody else there will be more about, we are robbed, we are exposed, we are irradiated, we have suffered, we are still suffering and I will die from cancer soon because of nuclear radiation… So it is not just my personal experience, I’ve been an academic who has seen a lot of research data, even data from Japan. They say that health effects due to radiation are not inherited. They keep the blood samples taken from the second and third generation offspring born to parents affected by Nagasaki and Hiroshima and spend $110, 000, I am not sure, monthly or annually, just to preserve these blood samples because present sophisticated methods, laboratory methods are unable to show any difference in their genomic/gene structure. The reason why they keep these blood samples is because they think maybe in the future more sophisticated methods will appear and they will show some changes which occurred in second and third generation offspring. The reason why I told you this now is that our people believe that nuclear effects are inherited; that children born from people who were exposed they are not healthy and grandchildren are also not healthy, although it is not official. It’s about fear.

And there is one more thing I will tell you. You know, Kazakhstan is extremely rich in uranium. We have 40% of the world’s uranium. And these uranium mines are located in East Kazakhstan. Now these two regions they merged together and these mines, they are still working, they are still open, they are active, we are never allowed to discuss this issue at all. Every year in August we have scientific conference on health effects related to ecological disaster, to radiation. We never discuss the situation with those miners although they continue working with this radiation mine, but they are affected, they are irradiated at present but they are invisible people – they don’t exist, their problems don’t exist.

There are international limitations to what amount of uranium ore you can sell. And Kazakhstan wants to sell more. The uranium we have is not the uranium suitable for weapons. It is good for atomic purposes. However, I don’t know I am not a physicist, a professional, I don’t know what you need to do but anyway you can increase its radioactive number and use this uranium after some sort of manipulations for weapons. So, Kazakhstan wants to sell more uranium, to be allowed to sell more uranium, we need to demonstrate that we are peaceful that we struggle with nuclear radiation and for no reason we should not be attributed to nuclear weapons production or nuclear weapons testing, explosions and all those things. There is another economic reason – we want to earn money.

"I started work at the Polygon in 1983 even before I was conscripted. After the navy, I came back and started working at the same mining organisation whose job was to drill the tunnels and galleries for the nuclear tests. I worked as a driver supporting the work of the mining workers, drove teams to work, equipment."

Edward Samtzov, driver in The Polygon, was interviewed in Kurchatov, Kazakhstan, May 2015, by Merilyn Fairskye, Translation: Ognian Pishev. (Edited)

In 1972, we arrived here, the whole family. It was a closed city under strict control; we had to fill in forms and then wait for 6 months for permission to relocate here from Almaty, where we lived. My father, who was a railroad worker and a specialist in railways, was invited to come and work here. There was a military unit to support the strategic aviation base in Chagan.

I went to school here. The town was growing and developing. After school I went to a vocational technical school, from that school I was conscripted to serve in the Navy.

I started work at The Polygon in 1983 even before I was conscripted. After the navy, I came back and started working at the same mining organisation whose job was to drill the tunnels and galleries for the nuclear tests. I worked as a driver supporting the work of the mining workers, driving teams to work, equipment.

When the (Chernobyl) accident happened, I was in the Navy. After that there were positions advertised. First, it was the job of the military to organise workers, and later we volunteered ourselves.There, I also worked as a driver transporting workers to the site as well as scientists. We lived in the actual exclusion zone. You may have seen the camp – immediately between Pripyat and Chernobyl.

When a moratorium on all work was introduced here in 1991, all the military units left the town and went back to bases in Russia. What you can see around is the work of the local population that couldn’t go anywhere else. Slowly we salvaged the town, those who didn’t leave, who had lived here since the founding of Kurchatov in 1948. Later, they organised the National Nuclear Centre. Funding was provided to restore the town. Now the Centre is the foundation of everything in the town. It is funding all work. It is a working polygon here. For young graduates after university – engineers, nuclear scientist, physicists, environmental scientists, radiologists - it is a real opportunity. There will be work for the next 300 years.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, I didn’t see big changes for the better, for the worse – yes! Life became more difficult, much harder. We had been used to the idea that someone else, somewhere was thinking for us, made all the decisions. We only had to carry them out. We didn’t build our lives, we simply followed orders to do things. We were conditioned to be like this since childhood. And when this whole thing fell through, we were no longer teenagers, so we had to learn how to live anew. Only now do we begin to understand what to do, how to live and the fact that we ourselves are responsible for our decisions and our acts – not someone else but we are the masters of our lives, and we must take matters into our hands.

It was like this

The artwork in Long Life is distilled from research and visual/audio material captured in the field, a process of looking, listening, building, assembling and disassembling.

Fieldwork is a mode of enquiry and not the artwork/experiment itself. The work that results is informed by being on site as well as by the raw material that results from being there.

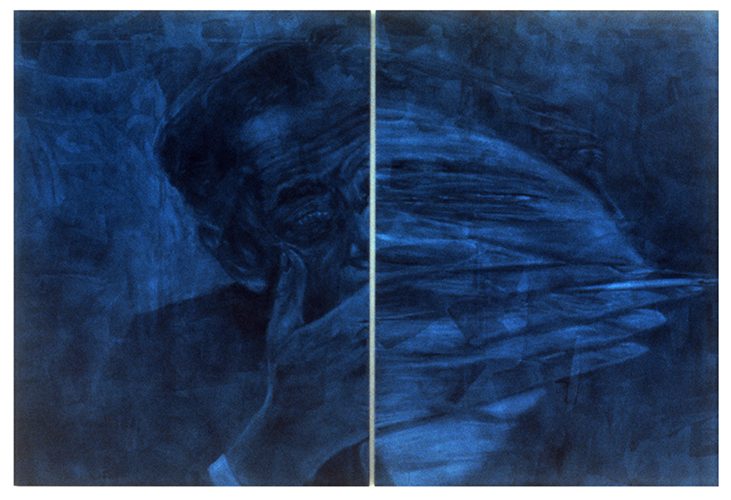

Merilyn Fairskye, 1992.

Tourquoise (J. Robert Oppenheimer)

from the

Smoke

series.

Two Panels. Oil and acrylic on canvas, 183 x 245cm.

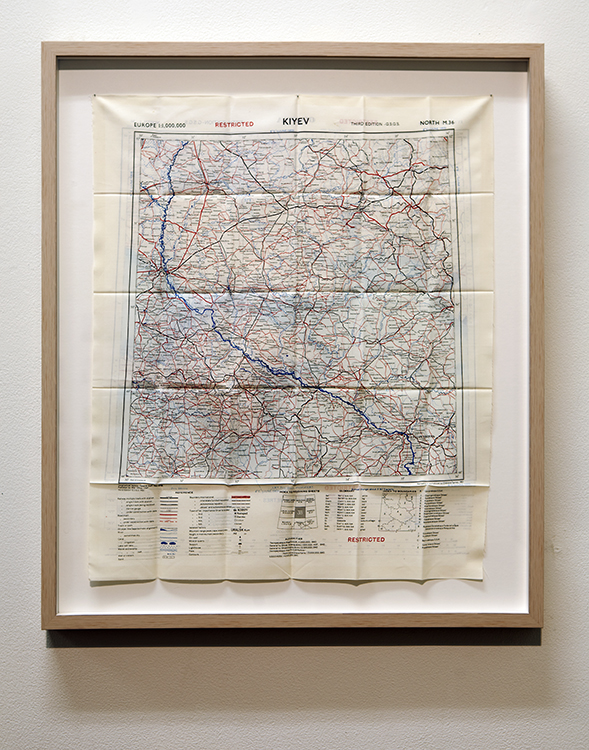

British War Office silk map of Ukraine

“I bought a silk map off the Internet. On one side it shows a detailed map of Crimea, on the other, Kyiv and surroundings. In the top left corner is the place name, Chernobyl. First published in 1947 by the British War Office, the map was issued to British military personnel engaged in covert actions in the Soviet Union during the post-war years. Entranced by the romance of the map, I decided to visit Chernobyl. I had no idea of the unsettling, shadowy world I was about to enter - the world of Long Life, and this evolving art project.” — Merilyn Fairskye

Watching, waiting for something to happen, the inevitability of a narrative unfolding across time, and imagining, projecting whilst looking at nothing - this is the nuclear experience. And the experience of this art project which considers the slow violence of critical technologies, through the lens of the second nuclear age.

The locales are sites of historic nuclear events; the environments irradiated, memory of the events dissipated, the original urgency long-gone. Apart from landscapes, residual traces and decaying structures, there is little to see. Radiation is invisible, and like memory, dissipates across time and space. Moving and still artworks, quasi-documentary, video installation, artist films, and photographic images, seen together disturb expectations of the spatio-temporal relationship between moving image works and the silent autonomy of the still image.

Today, the invisible is expressed everywhere: networks and cloud computing, social media, forms of communication, made visible as digital sequences on screen. An endless feed of content. Long Life demands a deeper, physical engagement that spreads into real space, over time, and makes the spectator part of an evolving situation in the exhibition space, and beyond the experience of looming ecological catastrophe, and the infiltration of technology into every aspect of the everyday world, including our bodies. Echoed in other anthropogenic disasters, the nuclear stands in for political, environmental, and personal apocalypse, unleashed by human actions, now beyond human control.

Merilyn Fairskye at Ground Zero, The Polygon

Merilyn Fairskye’s art has long engaged with real world issues that provide the backdrops to the lived experience of unseen or anonymous bodies that inhabit the socio-political landscape. Her practice, which traces the cultural, political and scientific webs that connect powerful events of real life, involves research, travel and the production of works that encompass a broad range of media and methods — from artist books to large-scale public artworks, to video installations, artist films and photo media.

The Long Life Project considers the slow violence of critical technologies across time and space, through the lens of the post-Cold War nuclear age. This website is both the portal to this work and the platform for new work. For over twelve years Merilyn Fairskye has visited nuclear sites to make art — in the US, UK, Russia and Australia including Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, Ukraine; The Polygon Nuclear Test Site, Kazakhstan and the Sellafield plutonium production reactors in the UK. From these visits, she has produced still images, video installations and artist films.

“I’m drawn to the things that can’t be pictured — atomic dreams and optimism gone awry, human fallibility and nuclear legacies, the ineffable relationship between people and place. And the deceptive, vulnerable beauty of many of the sites, often located in remote environments, and surrounded by secrecy. The visual drivers are the sites themselves, what is to be found there and what they suggest. The emotional driver is the underlying pathos of the brevity of human life set against the incomprehensible longevity of radiation." — Merilyn Fairskye

Merilyn Fairskye has participated in more than 175 curated solo and group exhibitions, nationally and internationally, over the past thirty-five years. Her art videos have been shown in prestigious film and video festivals around the world including the Al Jazeera International Documentary Film Festival, Doha; the International Film Festival Rotterdam; Videobrasil; Oberhausen Short Film Festival; Kassel Documentary Film Festival; Sydney Film Festival; and in exhibitions in art museums including the Museum of Modern Art, New York; Tate Modern London; the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney; Art Gallery of NSW; Songzhuang Art Museum, China and the National Palace Museum, Taipei.

Her work is included in museum, university, corporate and private collections including MoMA, New York; Getty Center, Santa Monica; and National Portrait Gallery of Australia; National Gallery of Australia; Parliament House, ACT; Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney; Art Gallery of NSW; National Gallery of Victoria; Queensland Art Gallery; Powerhouse Museum; Australian War Memorial; Art Gallery of Western Australia. It has been extensively written about in the art and general press. Fairskye has been the recipient of many Australia Council and Australian Film Commission grants, a Rockefeller Foundation Fellowship, a Fellowship at PSI Museum New York, and many awards. Her early artworks have had significant impact for curators and audiences long after their initial public presentation, and have been the subject of television documentaries and scholarly research.

Between 2000-2014 she taught at Sydney College of the Arts, University of Sydney, where she was Associate Professor, Media Arts.

‘In/Visible’, Unlikely – Journal for Creative Arts, issue 05

‘Uncertain Regard’, a paper delivered at Borderlands: photography and cultural contest – 2nd annual photography symposium, Art Gallery of New South Wales, 31 March 2012

Phillip Adams interviews Merilyn Fairskye, Late Night Live, ABC Radio National, broadcast Thu 17 Mar 2011

Tanya Peterson, Clear and Present Danger, Column 1, Artspace, Sydney